“It’s possible,” Tom DeMarco writes, “to make an organization more efficient without making it better. That’s what happens when you drive out slack.”

The myth of efficiency

The relentless pursuit of efficiency has the unintended result of eroding our effectiveness. Daily, our attention is consumed by the immediate and the urgent. Overall the consequence is less time spent thinking as we are consumed by doing. The capacity to think, create and innovate has been driven out of organizations along with the perceived slack. Somewhere along the line “slack” has become a bad thing.

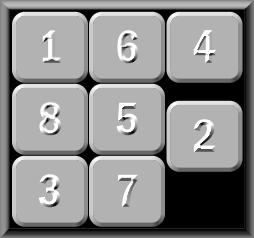

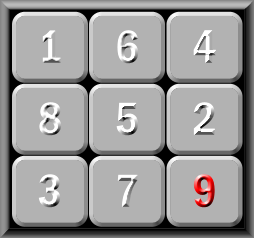

In his book Slack, Tom DeMarco illustrates the issue clearly with a simple puzzle. The challenge is to move the numbered tiles into numeric order.

In his book Slack, Tom DeMarco illustrates the issue clearly with a simple puzzle. The challenge is to move the numbered tiles into numeric order.

Filling the empty space achieves an impressive 11 per cent ‘efficiency’ gain but renders us incapable of solving the puzzle. We have no room to move. No slack.

The need for reflection

Our brains filter out most of the sensory data we encounter daily. Yet the connections we make between the information that does register don’t always happen automatically. Sometimes we need to think things through to build relevance, connections and insight in response to what we experience. For knowledge workers, in particular, this is critical. Gaining insight from thinking is hard cognitive work. We don’t respect the time and conditions needed to do it well. Interrupting a programmer who is working with a complex mental map of a system is guaranteed to cost time and effort to reconstruct the cognitive state he or she needs to work well.

To a degree, this is influenced by cultural norms. In some countries, a worker sitting quietly at his or her desk, deep in thought, is unlikely to be approached. In North America it’s an invitation to be interrupted.

Stop being busy

The inability to carve out time for reflection can be self-inflicted. We sometimes make poor choices about where to spend the currency that is our attention. A powerful ‘litmus-test’ is a simple question: “Is this useful or merely interesting?“ Pausing to ask this question can steer us to more effective use of our limited attention, time and energy.

Decide where to spend your attention

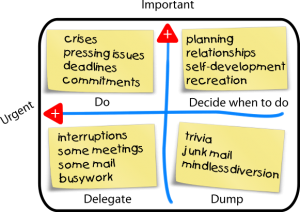

So how do we create slack for ourselves? There are many sources of advice on time management and setting priorities. Stephen Covey’s matrix has stood the test of time as a useful approach. Assessing activities by contrasting importance and urgency gives us a visual guide to what’s consuming our attention. Working to spend more time in the upper right quadrant (the reflection space) provides the slack we need to think about how to address the important and urgent events in our lives more effectively.

So how do we create slack for ourselves? There are many sources of advice on time management and setting priorities. Stephen Covey’s matrix has stood the test of time as a useful approach. Assessing activities by contrasting importance and urgency gives us a visual guide to what’s consuming our attention. Working to spend more time in the upper right quadrant (the reflection space) provides the slack we need to think about how to address the important and urgent events in our lives more effectively.