by Andrew | Jun 23, 2013 | Uncategorized |

When it comes to organizational change it’s becoming clear that using the word “manage” is inappropriate. At least five significant industry surveys in recent history have validated the outcomes of less than 30 per cent of change initiatives met their goals. (For example: Creating organizational transitions, McKinsey Global Survey Results, McKinsey Quarterly, July 2008.)

Expecting to manage change rests on an assumption that the process is linear – cause and effect are clearly linked and predictable. Seldom, if ever, is this the case in dealing with groups of humans. As a result, the typical top-down, carrot-and-stick approach to invoking change hasn’t proven to be very successful.

Most change efforts I’ve witnessed and participated in have been long on motivational effort and short on specific activity that increases the ability of people in organizations to change. Generally people aren’t averse to the idea of change but don’t much like the feeling of being changed. I think using different language will help.

We need to be having conversations that promote change and discuss how we can best accommodate and respond to change. As important as these conversations are, actions speak louder than words. As change advocates (or agents) we need also to model the responses we strive for and demonstrate support for the type of changes underway.

It’s important for people enmeshed in organizational change to know why this is happening – otherwise how can one commit to the desired outcome(s)? It’s critical however that we know how to change.

We’ve been having success with evolutionary approaches to large scale organization change using a collection of tools and processes we call Lean Change. If you’d like to learn more simply contact Leanintuit.

by Andrew | Apr 20, 2011 | Uncategorized |

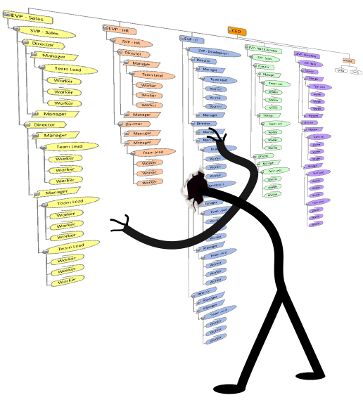

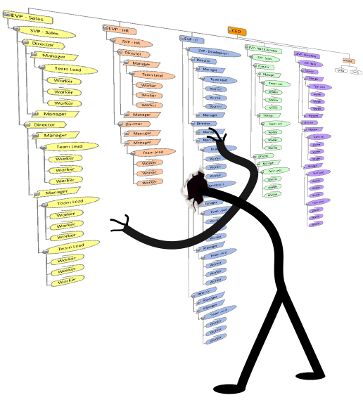

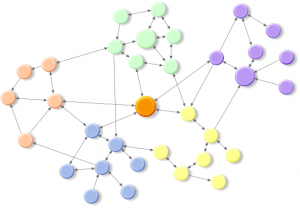

The most common maps of enterprises are hierarchical “organizational charts”. We see them everywhere. We depend on them to illustrate the structural elements of an organization and identify the people working within them. Their underlying organizing principle is top-down granting of authority.

Getting work done in organizations depends on relationships that traverse these artificial boundaries. Collaboration and “cross-functional” teams are a necessary feature of organizational life.

“… understanding how networks work is an essential 21st century literacy.” — Howard Reingold

A critical element of successful communication is knowing your audience. If you need to communicate important information and you’re relying solely on the corporate hierarchy to cascade it from the top, with the attention it deserves, I’d urge you to reconsider. Working with key influencers to craft “viral” messages can have far greater impact. Critical change initiatives need support from critical people. If you can’t identify them you’re flying blind.

The map is not the territory

If you think your organizational chart represents the relationships that get work done you need to pull your head out the sand (or the chart).

If you think your organizational chart represents the relationships that get work done you need to pull your head out the sand (or the chart).

It’s amazing how much attention is paid to the hierarchy documented in the organizational chart. All of us, when asked, will freely admit that the relationships required to get work done are not illustrated by an org chart.

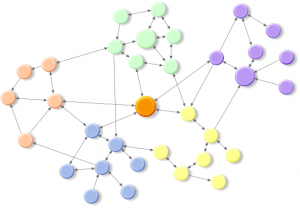

The reality of the modern organization is that it’s a network. It is the sum of social and working relationships that traverse both organizational silos and levels. The “old boys’ club”, the grapevine, even the smoker’s huddle indicate networks that use informal paths of communication to share trust, knowledge and support.

Organizational Network Analysis

Adopting a network view  is much more useful when it comes to understanding connections between people in organizations. We’re social and form relationships of commitment and trust we need to achieve both personal and corporate goals. This mesh of personal interaction isn’t revealed by an organizational chart but exists nonetheless.

is much more useful when it comes to understanding connections between people in organizations. We’re social and form relationships of commitment and trust we need to achieve both personal and corporate goals. This mesh of personal interaction isn’t revealed by an organizational chart but exists nonetheless.

Working with key or central people within these networks can amplify communication efforts, accelerate change and identify opportunities to promote development. If only we could identify them.

Making invisible connections visible

Tools and processes to do just that are readily available – Organizational Network Analysis or ONA. This type of analysis isn’t a new idea. It’s been used since the 1950s. Pioneers and advocates in the field like Valdis Krebs , Rob Cross and Patti Anklam, among others, have a significant body of experience in making invisible organizational links visible. Growing awareness and analysis of network dynamics has been sparked by internet communities like Facebook and LinkedIn. In parallel, Organizational Network Analysis adoption is finding new advocates. And new providers of tools, analytic software and services like Netview and Keyhubs are emerging.

This is an important and useful tool to consider when thinking about how to make your organizational development or communication initiatives work best.

by Andrew | Apr 7, 2011 | Uncategorized |

“It’s possible,” Tom DeMarco writes, “to make an organization more efficient without making it better. That’s what happens when you drive out slack.”

The myth of efficiency

The relentless pursuit of efficiency has the unintended result of eroding our effectiveness. Daily, our attention is consumed by the immediate and the urgent. Overall the consequence is less time spent thinking as we are consumed by doing. The capacity to think, create and innovate has been driven out of organizations along with the perceived slack. Somewhere along the line “slack” has become a bad thing.

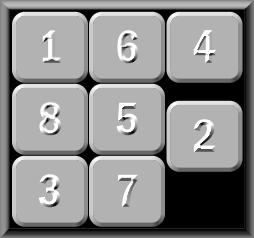

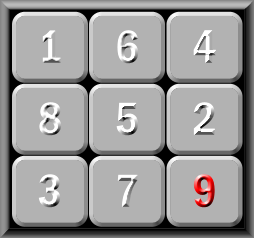

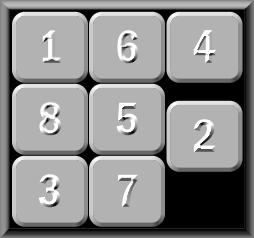

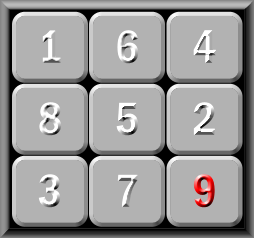

In his book Slack, Tom DeMarco illustrates the issue clearly with a simple puzzle. The challenge is to move the numbered tiles into numeric order.

In his book Slack, Tom DeMarco illustrates the issue clearly with a simple puzzle. The challenge is to move the numbered tiles into numeric order.

Filling the empty space achieves an impressive 11 per cent ‘efficiency’ gain but renders us incapable of solving the puzzle. We have no room to move. No slack.

The need for reflection

Our brains filter out most of the sensory data we encounter daily. Yet the connections we make between the information that does register don’t always happen automatically. Sometimes we need to think things through to build relevance, connections and insight in response to what we experience. For knowledge workers, in particular, this is critical. Gaining insight from thinking is hard cognitive work. We don’t respect the time and conditions needed to do it well. Interrupting a programmer who is working with a complex mental map of a system is guaranteed to cost time and effort to reconstruct the cognitive state he or she needs to work well.

To a degree, this is influenced by cultural norms. In some countries, a worker sitting quietly at his or her desk, deep in thought, is unlikely to be approached. In North America it’s an invitation to be interrupted.

Stop being busy

The inability to carve out time for reflection can be self-inflicted. We sometimes make poor choices about where to spend the currency that is our attention. A powerful ‘litmus-test’ is a simple question: “Is this useful or merely interesting?“ Pausing to ask this question can steer us to more effective use of our limited attention, time and energy.

Decide where to spend your attention

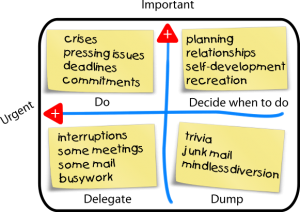

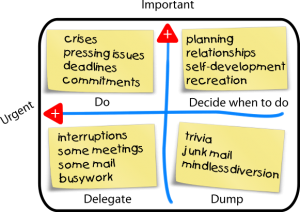

So how do we create slack for ourselves? There are many sources of advice on time management and setting priorities. Stephen Covey’s matrix has stood the test of time as a useful approach. Assessing activities by contrasting importance and urgency gives us a visual guide to what’s consuming our attention. Working to spend more time in the upper right quadrant (the reflection space) provides the slack we need to think about how to address the important and urgent events in our lives more effectively.

So how do we create slack for ourselves? There are many sources of advice on time management and setting priorities. Stephen Covey’s matrix has stood the test of time as a useful approach. Assessing activities by contrasting importance and urgency gives us a visual guide to what’s consuming our attention. Working to spend more time in the upper right quadrant (the reflection space) provides the slack we need to think about how to address the important and urgent events in our lives more effectively.

by Andrew | Jan 25, 2011 | Build your own skills |

Many of us are poor at accurately describing our emotional state. And worse at identifying other people’s. This can be unhelpful when we’re having a emotion-laden conversation.

I think it’s because we tend to have a limited emotional vocabulary. It’s hard to talk about things we can’t name. The words exist – in English there are a few hundred emotion words. The big ones are seldom a problem: joy, sorrow, anger, fear, disgust and surprise. It’s the subtler ones that often escape us. When we seldom use them it’s not surprising they don’t spring to mind when we need them most.

Our brains are highly attuned to the sensation of our own emotions and emotional signals sent by others. But when we’re asked to name these emotional states many of us stumble. It’s like trying to describe a colourful scene when all we know are names of the primary hues – the millions of shades we perceive but can’t easily name remain unmentioned. This can be a hurdle to understanding communication dynamics and to being understood. Especially when we’re not thinking clearly.

Here’s something that may help.

Psychologist Robert Plutchik proposed a visualization of eight primary emotions and their less intense variations arranged in a “colour” wheel that illustrates the interplay of core and related emotions. Using his “Multidimensional Model of the Emotions” we can “mix” emotions to express variations and nuance.

Note: This image has been attributed to Annette DeFarrari , here

Being better able to describe our own emotions lets us interact better with others. This tool can help us stretch our emotional vocabulary to enhance self-awareness and communication. Think of it as an exercise in emotional intelligence.

I hope you find it as useful as I have.

by Andrew | Dec 24, 2010 | Build your own skills |

“Procrastination is the thief of time.” – Edward Young (1683-1765)

We all do it. But for some, the practice of procrastination – delay without good reason, can become a chronic habit.

Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird , tells this poignant story of the consequences of delay:

“Thirty years ago my older brother, who was ten years old at the time, was trying to get a report on birds written that he’d had three months to write. It was due the next day. We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books on birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said, “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.”

We now know that procrastinaton isn’t a time management issue. There are powerful cognitive issues at play and our brains are not being our friends. But like any learned behaviour, we can displace it with another learned behaviour.

The irony of procrastination is that we succumb to it to feel better (in the short term) but the result is usually the opposite. Annoyance, stress and guilt quickly erode the fleeting sense of satisfaction provided by the distraction of the choice we make in the present moment. Procrastination simply doesn’t make us feel great. This distress seldom prevents the development of a procrastination habit.

A good place to begin

Whatever it is you need to get done – just start. Then revise and improve.

You need to give yourself permission to do less than a perfect job on the first pass. It’s considerably easier to edit, expand or criticize something than it is to wait in suspended animation with nothing in hand.

The key is to assess, realistically, the cost of delay – to you and others. There are many reasons to delay starting. But, at least for me, the fleeting pay-off of delay seldom exceeds the cost of anxiety.

Two inspirational resources

If Google search results are any indication, I’m convinced interest in conquering the scourge of procrastination ranks with achieving world peace. But among the overwhelming options here are two resources that I’ve found enaging and useful:

Dr. Timothy Pychyl has spent his career exploring procrastination. He makes his research accessible to those who need practical guidance through his blogging at Psychology Today and now, in an excellent short ebook called The Procrastinators Digest. If you want to understand and counter procrastination tendencies I think it’s the best $2.99 you could ever spend.

Dr. Piers Steel conducted a meta-survey of formal academic publications that analysed over 800 scholarly papers on procrastination. This effort, along with his own research, has provided the insight he shares in his new book The Procrastination Equation (available December 28, 2010)

In it Steel debunks long-standing theories (and myths) regarding procrastination and proposes a new explanation that provides guidance towards overcoming our tendencies to delay. Based on previews and testimonials alone, this is not to be missed if procrastination is on your mind.

If you’re keen to see where you rank in Steel’s procrastination continuum and are willing to further his research you can take his survey.