by Susan Johnston | Jan 9, 2016 | Build your own skills, Get people talking |

Ten years ago, my writing and conference talks were filled with predictions that conversation would be the Next Big Thing.

2007

Citing evidence from multiple disciplines, I called for organizational leaders to recognize that the desire for connection is a basic human trait and make in-person interaction a deliberate priority. Instead of trying to master blogs, podcasts, email and other tech-centric communication channels, I urged them to get out and talk to people.

But Next Big Thing would not be face-to-face communication. In 2007, along came the iPhone. Mobility became the NBT. And our world changed. Today, our mobile devices keep us “connected” and “talking” to people around the world 24/7. Yet, is it a true connection?

In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York), sociologist/psychologist and MIT prof Sherry Turkle suggests our “always on” connections, such as facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thousands of other apps, provide the illusion of communication, but actually impede conversation. We can avoid real conversation by sending a text. We can post a picture rather than engage with someone. We can edit ourselves into a carefully constructed persona that presents someone we are not and will never be. We can post messages to facebook “friends” while ignoring the real friends in the room with us. We can get attention without the unpredictable untidiness of getting close.

In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York), sociologist/psychologist and MIT prof Sherry Turkle suggests our “always on” connections, such as facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thousands of other apps, provide the illusion of communication, but actually impede conversation. We can avoid real conversation by sending a text. We can post a picture rather than engage with someone. We can edit ourselves into a carefully constructed persona that presents someone we are not and will never be. We can post messages to facebook “friends” while ignoring the real friends in the room with us. We can get attention without the unpredictable untidiness of getting close.

A Gloomy Outlook?

Turkle has spent 30 years investigating our society’s relationship with technology. In this book, her ninth, she descibes offices where workers lay out their multiple devices, don headphones and spend the day exchanging electronic messages in isolation. She describes the “rule of three” – as long as three people in a face-to-face group are actually talking to each other everyone else can be looking at their phones. She quotes people who conduct family discussions by text so they can “fight without saying things [they’ll] regret” – and have a record of who said what. She describes toddlers competing with mobiles for their parents’ attention, new moms texting while nursing newborns, and children who talk about what’s on their phones rather than what’s in their heads. What worries her most is her belief that we are losing the ability to hold real, meaningful conversations.

IBM’s PROFS

Turkle’s work made me examine my own relationship with online communication tools. I’ve used them since pre-Internet days, when I sent email-ish things on the green screens of mainframe terminals. Today, I used tools in “The Cloud,” wherever that is, that we could scarcely imagine 10 years ago – Slack, Twitter, Trello, Ruzuku, Zoom and more. (I’m still waiting for “Beam me up, Scotty.”) They’re handy, yet today’s most valuable and rewarding connections were in cafés, face-to-face with colleagues and clients. I could look them in the eye, feel their energy, sense their presence, offer my full attention and really be with the people I chose to be with.

Text is fine for transmitting information, but it’s not the tool for real communication. A recent text exchange led friends to a weird misunderstanding. Words intended as heartfelt encouragement came off as preachy. The carefully crafted response was interpreted as a snotty retort. Nuance, subtlety, emotion, energy – all missing. Words are not enough. How often have we spent hours crafting careful responses to emails when we should have just picked up the telephone and sorted it out through conversation?

So what can we do?

Which brings us back to Turkle and Reclaiming Conversation. She paints a bleak picture, yet offers hope. We don’t need to give them up, but we need to choose how we use these devices. We can designate tech-free zones, declare a mobile moratorium during meals, establish no-device hours, banish them from meetings. She writes, “If a tool gets in the way of looking at each other, we should use it only when necessary. It shouldn’t be the first thing we turn to.”

We can ask ourselves if our relationship with technology is helping us live better, more fulfilling lives or getting in the way of important moments and real connection. Our insights about the way we use our tools will guide us. The art – make that the gift – of conversation is too important to lose.

Can we talk? Getting back to conversation – Part 2

by Susan Johnston | Jun 9, 2015 | Uncategorized |

Yesterday, at Agile Coach Camp Canada, I had the privilege of leading a group conversation about taking care of yourself as a coach.

Yesterday, at Agile Coach Camp Canada, I had the privilege of leading a group conversation about taking care of yourself as a coach.

The Big Idea is like the instruction flight attendants give us, “If you are travelling with a child or someone who requires assistance, secure your mask first, and then assist the other person.” As coaches – or as anyone – we don’t have much to give others if we don’t take care of ourselves.

The coaches who gathered for the session agreed that people attracted to the work of helping others often put our own needs behind those of our teams and our organizations. That habit can result in fatigue, stress, and burnout. It impacts relationships both at work and at home.

Here’s the list we built in the conversation:

What can we do to take care of ourselves?

Notice when you’re feeling depleted.

Show yourself some compassion.

Give yourself some space.

– Close the door

– Go for a walk – preferably outside, in a pleasant place

– Physical activity – “I bike to work.”

– Announce it, in a light way. “I let the team know I may be a bit of a Grumpus today.”

Do something you enjoy and are good at

– “I do some real, individual coaching. That lets me see I’m making a difference. It’s almost like a gift to myself.”

Use your network

– “I call another coach and I know I’m not in this alone.”

– “I get coached myself. It’s time I have to focus on me.”

Make your work and success visible

– Personal kanban

– Read your fan mail

– List your successes

– Find a win, however small

Spend some time in reflection

– Journalling

– Mindfulness practice

Let people know what’s fun for you

Manage expectations

– yours and others

– “Accept that our work is messy and it’s a journey.”

Say “no” to more work

– “If you can’t say “No” then your “Yes” can turn into a “Maybe” ”

– “I’d rather disappoint you now, with a “No,” than disappoint you later by being unreliable.”

Gratitude

– Think of things you’re grateful for

– Practise thanking – and accepting thanks

– Appreciate it when others thank you – and show it

– Savour the kudos

Know your purpose and only do what’s aligned with that

Spend some time just doing nothing

– “The brain needs to rest just like any muscle.”

Hugs

– More hugs

One in our group, Gitte Klitgaard, was on her way to a tech conference in New York where her talk was “Stress and Depression – The Taboo and What We Can Do About It.” A link to an earlier version of that talk is at vimeo.com/106927863

Our conversation reminded us that we need to recognize we’re human and show ourselves the empathy and compassion we show our teams and coaching clients.

Note: If you are an agile coach and have never been to an Agile Coach Camp, plan on attending one when you can. They are impossible to describe and they are amazing. There’s one, this weekend, in Calgary, Alberta and one coming up in Washington, DC, August 1st.

by Susan Johnston | Mar 20, 2015 | Uncategorized |

With just over a month to go till the Spark The Change conference, I’ve been thinking a lot about change in the workplace.

As an organizational communicator – and even as a coach – my work has always been about change. “Everything is the same as it was yesterday,” is not a message I’ve ever sent, or even heard. While “no change” may be a true reflection of the situation, it’s not something we shout about. Even when we wish things would just stop changing for a second, while we catch our breath, we know it’s not realistic. When markets, environments, regulations, politics, consumer preferences, off-shoring, competitors, technology and a zillion other factors demand that we adjust and respond, not changing is not surviving.

But how do you do it?

We know what doesn’t work.

Scare tactics

When I first worked in change management, in the late 1980s, my organization hired high-priced consultants to tell us what to do. The prevailing idea was, “Scare people into changing.”

I recall the mantra, “Change or Be Changed.” I’m sure I wrote it into several executive speeches and articles for assorted publications. The idea was that, if we don’t voluntarily change the way we do things, something will come along and force us to do it. Might as well do it now than go kicking and screaming. Or maybe we could do it next week. What’s wrong with a good kick and scream?

We told stories about the “burning platform,” in which a worker caught on a blazing North Sea oil rig chose probable death over certain death, jumped off the drilling platform into the icy sea and was rescued. Only a blaze would have caused that behaviour change. This story was designed to get us to develop a sense of urgency around the need to change. But when employees look around and see that you have lots of customers, you’re raking in profits, nothing seems to be changing except the rhetoric and your CEO is taking a million dollar bonus, things don’t look particularly urgent.

One consultant trotted out my old friend Kurt Lewin, from Psychology 315 and his metaphor of ice. If you want the ice to change from a cube to a pyramid, you have to unfreeze and refreeze it in the new shape. (Could we use the burning platform to melt it?) We’d have to give up cherished beliefs about our selves and our organization and challenge the status quo. Not easy for executives and managers who were very well treated by the status quo. While we were sloshing around in that liquified state, waiting to refreeze into the new status quo, things would be chaotic, disordered and generally awful. No wonder people resist change.

Yes, we would meet resistance. Yet we knew (as the Borg kept telling us on Star Trek) “Resistance is futile.” The favoured model of resistance was the (Elizabeth) Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle, in which someone needs to pass through Denial, Anger, Depression and Bargaining to get to Acceptance. Why grief? Well the old ways were dead. We needed to mourn and move on. I remember thinking that, even though I understood the “why” for change and was 100 per cent behind the notion that we had to do it, I was, nevertheless, resisting. I wanted proof we would actually do it and that it would work. More than that, I wanted someone else to go first. I don’t think I got past Bargaining. And if I, the Change Girl, wouldn’t go, who else would?

Communication was acknowledged to be a key success factor or I wouldn’t have been involved. The why of the change wasn’t hard to describe. But what and how were a mystery. I’d prepare messages that reflected what employees wanted to hear, which was, “This is going to be hard but here’s how we’ll support you.” Then I’d prepare messages that reflected what executives wanted to say, which was mostly, “Bla bla bla.”

Appreciative Approach

What I wish we’d known about in those old days of “change management” was how to take an appreciative approach. Instead of scaring people into different behaviours, why not unleash them to find their own way? While we were freezing and burning and and resisting things, a grad student named David Cooperrider was “unfreezing” our notions of change. His process, Appreciative Inquiry, shifts organizational change from a problem to be solved to a creative endeavour. We ask questions about what’s working and have conversations about how we got that and how to get more. It sees the organization as organic, alive and able to change because it has done so in the past. By examining what is right and good, people are reminded of their abilities and resilience. They have more confidence and comfort to journey into the unknown future when they bring forward known parts of their past.

New ideas and tools

Appreciative Inquiry is just one of many tools we have today that we didn’t know about in the ’80s. We also have the benefit of knowing, thanks to advances in neuroscience, how human brains work. And we can talk about how we feel about change, thanks to the widespread acceptance of emotional intelligence as a factor in success.

I’m looking forward to Spark The Change, April 23, in Toronto where I expect to collide with people from diverse disciplines and types of organizations who want to create better workplaces. I’m anxious to hear new ideas from speakers who aren’t just talking about change, they’re doing it. I know we can create organizations that not only operate more successfully as enterprises but are also saner places to work.

by Susan Johnston | Dec 19, 2014 | Uncategorized |

When I first studied accounting I was astonished that “goodwill” is something you can quantify and express with a financial value. I’d always thought of it as kind thoughts towards my fellow humans. Those are valuable, for sure, but not exactly something you can put a dollar sign on.

When I first studied accounting I was astonished that “goodwill” is something you can quantify and express with a financial value. I’d always thought of it as kind thoughts towards my fellow humans. Those are valuable, for sure, but not exactly something you can put a dollar sign on.

Along come generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to tell us that goodwill isn’t just about benevolent feelings towards others. It’s also the amount one company pays to buy another that’s over and above the tangible value of the assets being acquired. How could a company be worth more than its tangible assets? A strong brand, customer relationships, intellectual property and existing contracts might qualify as goodwill. It sits on the balance sheet as an intangible asset.

It’s interesting to ponder the value of goodwill during this season of “Gloria. Peace on Earth to men of goodwill.”

Goodwill, the kind thoughts variety, makes us worth much more than our tangible assets. It connects us to others, something we need to keep us human. There’s ample evidence of a link between the mind and the body that suggests positive thoughts and acts of generosity lead to more than just good feelings – they promote physical health. The explanation is that reciprocal benevolence kept our ancestors alive back in the days of “kill or be killed.” So we’re wired to be kind to each other.

You might argue that we don’t have to look far to find people whose learning or circumstances and choices override that basic human inclination towards goodwill. We see the impact of extremism and zealotry on the nightly news.

As I write that, I’m reminded of a quote from Anne Frank, who wrote, as she was hiding from the Nazis, “Despite everything, I believe that people are really good at heart.”

We can choose goodwill. Each of us can do our own bit to look for the best in others. As coaches, it’s our job to not only see their best but also to help them see it – and do something with it. Anne Frank said it best, “Everyone has inside of him a piece of good news. The good news is that you don’t know how great you can be! How much you can love! What you can accomplish! And what your potential is!”

This is a series inspired by House of Friendship Kitchener’s 12 Days for Good project. There’s a theme for each of the 12 days – no pipers piping required. Learn more at http://12daysforgood.com

by Susan Johnston | Dec 13, 2014 | Uncategorized |

“Safe travels!” We hear that a lot, this time of year, when folks head off for the holidays. What does it mean to be safe?

“Safe travels!” We hear that a lot, this time of year, when folks head off for the holidays. What does it mean to be safe?

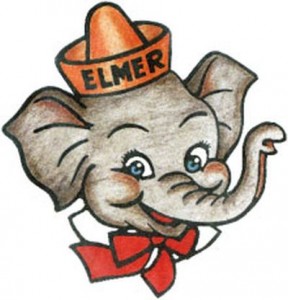

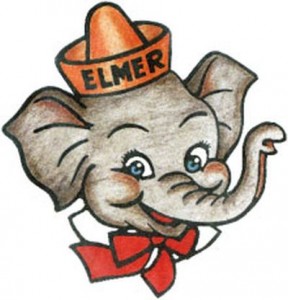

My first official memory of safety involves Elmer the Safety Elephant. We met him in kindergarten and he was a fixture in our primary and elementary school lives. Since “an elephant never forgets,” Elmer’s job was to remind us to be careful. He had his own flag and it was a big deal to help put up the Elmer flag every day, signalling that the school had been accident free. He had five safety rules:

- Look both ways before crossing the street.

- Don’t go between parked cars.

- Ride your bicycle safely and obey signs and signals.

- Play games in safe places, away from traffic.

- Walk, don’t run, when you leave the curb.

Elmer was born in Toronto in 1947, through a collaboration of the mayor, the police department and one of the daily newspapers. This vintage CBC video tells the story. (It’s worth a peek just to see the cars.) Child accidents declined and word spread across the nation. A national program followed and children in the hinterland, like me, got to meet him and learn and practise his five rules.

“Whatever happened to Elmer?” I wondered, this morning. Well, boys and girls, he’s still around. Like so many other celebrities, he’s had a facelift to counteract the effects of aging. And today, in addition to traffic safety, he now dispenses wisdom about fire safety, railway safety and Internet safety.

As adults, how do we channel our “inner Elmer?” Safe driving, snow tires, shovelled sidewaks, fresh batteries in the smoke detectors, holding the handrail and, yes, looking both ways – all these promote physical safety for ourselves and others.

I also think about another sort of safety.

- How do we make it safe for people to express themselves?

- How do we encourage people to listen to ideas with open minds?

- How do we encourage people to speak up about things that matter and ask questions about things that puzzle us without fear of being judged, labelled and dismissed?

One way to do that is to be conscious about our communication. We can assess the impact of our words before we speak them. We can share the intention that lies behind them. We can listen to understand, rather than simply to respond.

We create a climate of safety. Just like Elmer.

This is a series inspired by House of Friendship Kitchener’s 12 Days for Good project. There’s a theme for each of the 12 days – no geese-a-laying required. Learn more at http://12daysforgood.com

In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York), sociologist/psychologist and MIT prof Sherry Turkle suggests our “always on” connections, such as facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thousands of other apps, provide the illusion of communication, but actually impede conversation. We can avoid real conversation by sending a text. We can post a picture rather than engage with someone. We can edit ourselves into a carefully constructed persona that presents someone we are not and will never be. We can post messages to facebook “friends” while ignoring the real friends in the room with us. We can get attention without the unpredictable untidiness of getting close.

In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York), sociologist/psychologist and MIT prof Sherry Turkle suggests our “always on” connections, such as facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thousands of other apps, provide the illusion of communication, but actually impede conversation. We can avoid real conversation by sending a text. We can post a picture rather than engage with someone. We can edit ourselves into a carefully constructed persona that presents someone we are not and will never be. We can post messages to facebook “friends” while ignoring the real friends in the room with us. We can get attention without the unpredictable untidiness of getting close.