SCARF is a concept developed by David Rock of the NeuroLeadership Institute and popularized in his book, Quiet Leadership. It’s a good way to take stress out of a conversation. That’s useful, since a person in stress doesn’t think clearly.Sometimes, our brain is not our friend.

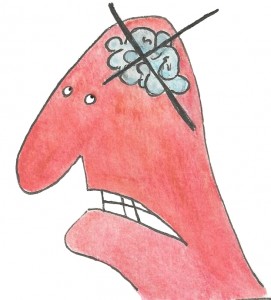

SCARF is a concept developed by David Rock of the NeuroLeadership Institute and popularized in his book, Quiet Leadership. It’s a good way to take stress out of a conversation. That’s useful, since a person in stress doesn’t think clearly.Sometimes, our brain is not our friend.

There’s a busy and primitive part of it, the amygdala, always scanning for changes in the environment. It interprets all change or discomfort as danger, which made sense when the User Guide for Life  was: “Eat or be eaten.” When the part of the brain concerned with survival takes over, the “fight or flight” mechanism kicks in automatically. The part of the brain that processes information and makes decisions is all but shut down as the body involuntarily prepares for trouble.

was: “Eat or be eaten.” When the part of the brain concerned with survival takes over, the “fight or flight” mechanism kicks in automatically. The part of the brain that processes information and makes decisions is all but shut down as the body involuntarily prepares for trouble.

The theory suggests there are five elements of a relationship or situation that can derail any conversation if they are missing or out of balance. The more we can do to provide them, the more likely the other person is to feel safe in the conversation and able to think clearly.

You won’t be surprised to learn that SCARF is an acronym.

STATUS – “Where am I in the pecking order?” Our brains are always on the lookout for evidence of where we sit regarding power, authority and influence. That’s residue from an earlier time, one that held greater risk of getting clobbered. We feel safer when we sense that our status is equal to or greater than the folks around us. Neuroscience suggests that our brains react to a threat to our status the same way they do to a physical threat. The brain doesn’t differentiate. So if you “outrank” the person you’re talking with – you’re their boss, professor, parent, etc. – the very fact of talking with you is stressful because your status is higher than theirs.

What can we do to balance the status? Recognizing the gap is the first step. You might move the meeting from your office to a neutral place or a place where they are comfortable. A conference room, a cafe, their office or go for a walk. You might draw their attention to a fact that raises their status. “I need to talk with you because you have experience with this project.” “Your job gives you a closer look at [whatever], so I value your thoughts.” “As a member of this team, your work is important to our success.” Make it something real – they’ll smell inauthenticity.

CERTAINTY – The brain that sees change as danger likes to know what’s coming. A reliable pattern signals safety. Letting people know what’s ahead helps. You might let them know how the conversation will go. “Let’s hear your view of things. Then I’ll share mine. And we’ll decide together how to handle this.” “We’ll brainstorm for 20 minutes or so, then I’ll make the decision.” Simply stating the objectives of a meeting can go a long way to removing uncertainty. If you’re like most people, you want to know why you’re in a meeting so you know how to behave.

AUTONOMY – Few of us like being told what to do and how to do it. We like to feel we have some control over what we’re doing or some choice about what happens. In a conversation, you can provide autonomy by allowing the other person to choose when and where to talk. They might also choose what to talk about first and what outcome they want from the conversation. (That’s one reason Lean Coffee works so well.)

RELATEDNESS – This is about whether someone is one of us, a member of our tribe, friend or foe. The decision about someone’s affinity or belonging affects how we think and feel about them. It’s hard to feel empathy for someone we think is our competitor. Trust is stronger when we feel someone else is part of our group. In conversations, to increase relatedness, look for what you have in common, shared objectives, similar goals. And use “we” language, rather than the language of “I” and “you.”

FAIRNESS – When we think about fairness, we may picture a petulant four-year-old stamping her foot and saying, “That’s not fair!” Yet fairness is a strong motivator in adults, too. The perception that something is unfair can trigger negative emotions, including disgust and a reduction in empathy. Transparency can minimize the negative impact of perceived unfairness. Let people know what’s going on and why.

SCARF may look like a big, long process, but it’s actually more of a checklist. Ask yourself if the other(s) in your conversation might feel a threat from each of the elements. Then ask yourself what you can do to reduce the threat.