In Being Wrong – Part One, we looked at some of the reasons – both innate and learned – that contribute to our “need to be right.” In this post, we’ll look at some things we can do to stop it from getting in the way of good decisions.

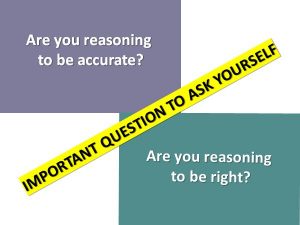

One of the first things we can do is to be aware of whether we are reasoning to discover something or to confirm something we already believe.

Whether we’re playing poker, building software, introducing organizational change or deciding which checkout line to go into at the grocery store, we’re working with incomplete information. There is lots of uncertainty. Lots that we can’t control, no matter how smart we are.

Thought experiment

- What was the best decision you made in the past year?

- What was the worst decision you made in the past year?

- (What was your process for making each decision?)

Today’s environment, for work and for life is volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous. We can’t be certain how anything we plan will actually turn out. Still, we have to take a chance and bet on something.

We can develop practices that will help us overcome our habits and biases so that we improve the odds in our decision making. Help us make better bets.

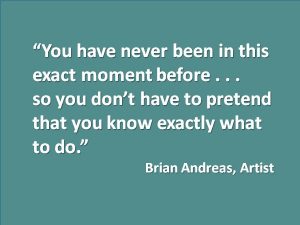

One recommendation is to cultivate what are called “Negative capabilities.” It’s a strange label because there is nothing negative about these traits except they are less visible and action oriented than those normally associated with success. They’re not the sort of thing we normally put on our résumés. It was the poet John Keats who first used the term and it’s been adopted by psychologists (such as Wilfred Bion) to indicate openness of mind, the ability to tolerate the pain and confusion of not knowing, rather than trying to be certain in an ambiguous situation.

They’re not the sort of thing we normally put on our résumés. It was the poet John Keats who first used the term and it’s been adopted by psychologists (such as Wilfred Bion) to indicate openness of mind, the ability to tolerate the pain and confusion of not knowing, rather than trying to be certain in an ambiguous situation.

Both “positive” and “negative” capabilities are needed to create a space of learning and creativity.

Source: French, Simpson, Harvey – “Negative Capability: A contribution to the understanding of creative leadership” (2009).

You exercise these negative capabilities when you challenge your beliefs

- What are some of your typical reactions when you come to the edge of your knowledge and expertise?

- What might you begin doing if you were not afraid of looking or being incompetent?

- When was the last time you said, “I don’t know?”

- What would be a safe context in which you might express doubt?

- How could you test your assumptions?

- How might you show more compassion to yourself and others when facing the unknown?

Source: D’Souza & Renner – “Not Knowing” (2014).

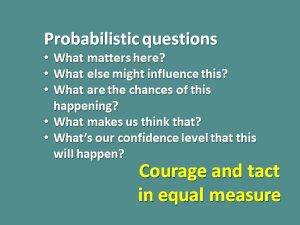

Decision making can be improved by adopting probabilistic thinking. This is essentially trying to identify the most likely outcomes of a course of action. Data specialists use modelling tools, math and logic to estimate the likelihood of any specific outcome coming to pass. I’m not advocating for us all to go out and become data scientists, but we can make an effort to calculate the odds in uncertain situations and assess the risk of choices. This is a good team or group exercise.

The first question to ask is, “What matters here?” You want to the identify situational conditions that will affect the outcome – as many as you can.

For each one, ask “What are the chances of this happening?” based on your knowledge of the facts relating to that condition and actual experience in similar situations. Attach a confidence level. “How confident are you?” (You could use your Planning Poker cards.)

Identify the assumptions you’ve made and assess their reliability. Think about any cognitive biases that might be at work. Then make the decision.

Watch your language

- Ask humble questions, not rhetorical or smart-alec questions.

- Challenge your own ideas – train yourself to test alternate hypotheses

- Focus on accuracy

- You might be wrong

- Be open to diverse viewpoints

- Work in groups – easier to see others biases than our own.

- Give everyone permission to ask, “What are we not seeing? And why?”

Other sincerely curious questions

- What is likely to happen if we do X? What’s our level of confidence?

- How do we know? What’s our evidence?

- What would need to be in place for that to work?

- What else might be true?

- How can we find out?

- What are we not seeing?

- Are we examining for discovery or for confirmation?

- What biases do we have that might lead us astray?

Use the team. You might build this sort of questioning into your team agreement so curiosity and humility become the norm. It will help you go from trying to be right all the time to seeing a more accurate and objective representation of the world.

Developing the habits of exposing our thinking, acknowledging and neutralizing our biases, and recognizing the value of not having all the answers requires deliberate, conscious practice. It’s worth it. It calls for courage and tact in equal measure. It wakes up our brains so that we build a better foundation for our bets.

Sometimes the smartest thing you can do is give up the need to look smart.