This post is based on a presentation Sue gave, in 2021, at an internal Agile conference at one of the Canadian banks.

I’m willing to bet that you’ve discovered that your interactions with colleagues and other departments are as important to Agility as the work you do. It often is the work.

Communication is key to our collaborative and iterative way of working. And sometimes it doesn’t go so well.

Sometimes, we get in our own way, trapped by a very human desire to look smart that impedes our decision making.

In this post, we’ll look at ways you can limit their influence. We’ll answer the question, “What if the smartest thing you can do is give up the need to look smart?”

First – a thought experiment. Think about the way you drive. Are you better than average, about average, or worse than average?

Would it surprise you that something like 80 per cent of people believe they are better than average drivers? It cannot be true. Do the math.

This phenomenon has been validated by lots of research. Eighty-seven per cent of Stanford MBA students believe they are smarter than others in their program. This trait shows up in studies of stock traders and lawyers. Worse, Kruger & Dunning, discovered that people who considered themselves the smartest in their groups were, in fact, at the bottom.

This phenomenon is known in social psychology as “illusory superiority.” We overestimate our own ability in relation to the same thing in other people. And we underestimate theirs.

Illusory superiority is one of many cognitive biases affecting decision making. Consider, for a moment, where illusory superiority may or does show up in your life. In your work. On your team.

So, it seems there’s a natural human trait that makes us think we’re smarter than we are. And our brains support us in this.

Because our brains are lazy.

Legions of neuroscientists have hooked human brains to technology that shows our brains are set up to expend as little energy as possible. There’s no shame in this. Our earliest ancestors needed that energy for survival in a harsh world beset with predators and lots of danger. They had to muster the physical and mental capacity to always be ready to fight or to flee – and to decide in a split second, which of those was the better option. Their brains didn’t have time to think things through and, instead, they took shortcuts.

Centuries later, your brain still does this.

In his book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman describes experiments that show how our brains resist processing new information. Our brains see patterns, sense similarities and use memories of familiar patterns to guide our behaviour. It’s almost automatic, beneath our awareness.

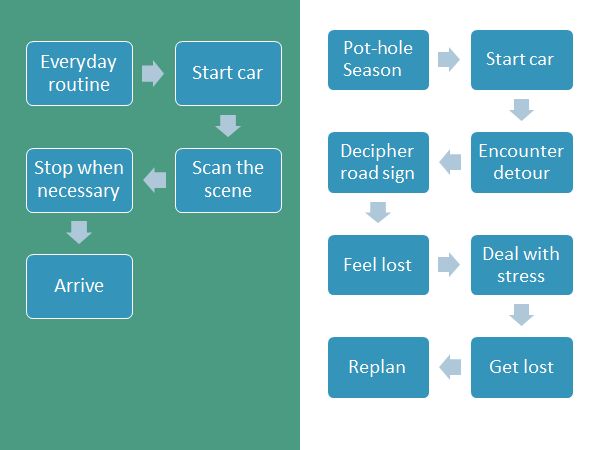

Let’s go back to driving, if you travel the same route every day, beyond watching the road, you may not be aware of your actions. Your brain doesn’t have to work at thinking. It uses well-worn neural pathways to respond quickly and guide you from start to finish without using up energy. But if there’s a detour and you need to follow signs, your brain must work to process new information. And it’s a slower, more challenging, process since your brain hasn’t done this before. It must take the energy to consider the info and make decisions.

Here’s another thought experiment. How can you tell a dog’s age? Well, you take its chronological age and multiply by seven. How do you know? Everybody knows that. Really? Turns out it’s wrong. But our lazy brains believe it because we heard it somewhere. Rather than challenge the idea, do some research, or even think about it, we bought the idea. After all, it made sense.

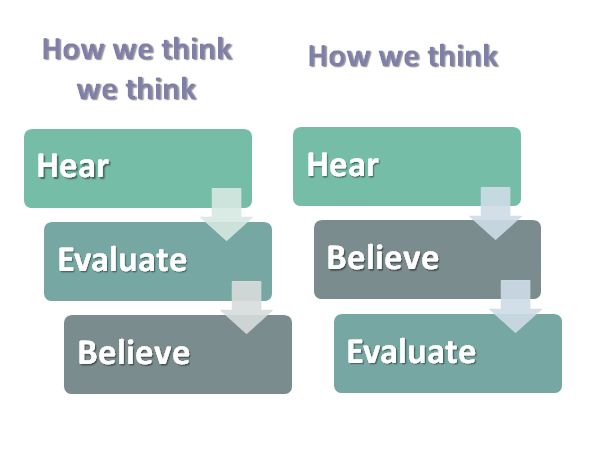

Our brains fool us that way. We assume it works like this. We hear something. We evaluate it. We believe it. What’s really going on is this. We hear something. We believe it – especially if we hear it from someone we trust, someone in authority, or someone like us. Then we evaluate it. When we get around to it. If we have time. Later. Maybe.

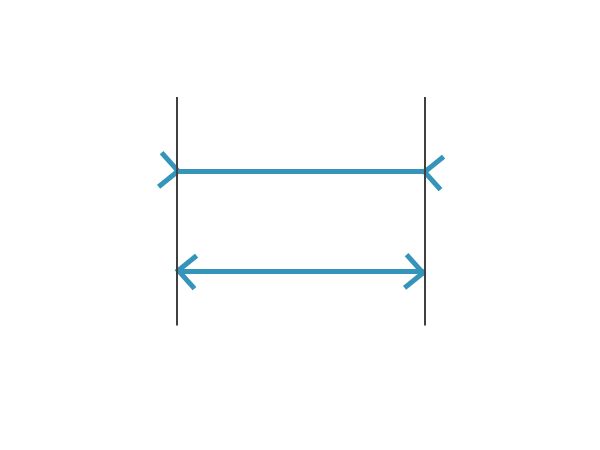

Our brains also make stuff up. There’s a well-known optical illusion where two lines of equal length look very different because the ends of one point inward and the ends of the other point outward. The outward pointing line appears longer. Measure the lines and you see they are the same length. But our brains have trouble with that.

This illusion is an example of another cognitive bias. Confirmation bias. Even when we have evidence that something else is true, we still may have a hard time believing it.

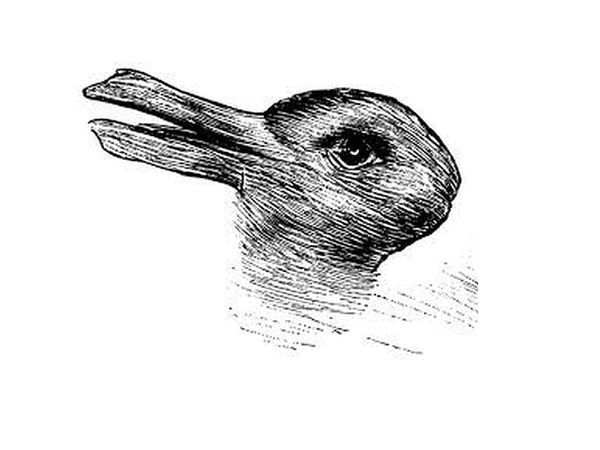

Your brain may also misperceive things, especially when information is incomplete. It’s looking for patterns. In this illustration, what creature do you see? Is it a rabbit? Is it a duck? Who knows?

This bunny/duck dilemma also reminds us that every brain is different. The way you perceive and believe things affects your decisions and behaviour. This is relevant to collaboration – a key element of working in an Agile fashion.

If I see things one way and you see them another, the conversation can get messy and collaboration’s at risk because of another human characteristic – the need to be right.

The brain’s discomfort with information in patterns it doesn’t recognize is one of the reasons people may resist new ideas when they’re first presented. The brain will often ignore new information. It’s uncomfortable to think through something new and different. It uses up resources. Once we decide something is true, we really don’t want to change our mind about it. That’s another cognitive bias.

It gets worse. Even when we look for the truth, we’re often really looking for support for our own existing beliefs.