Addressing the Agile Elephants in the Room

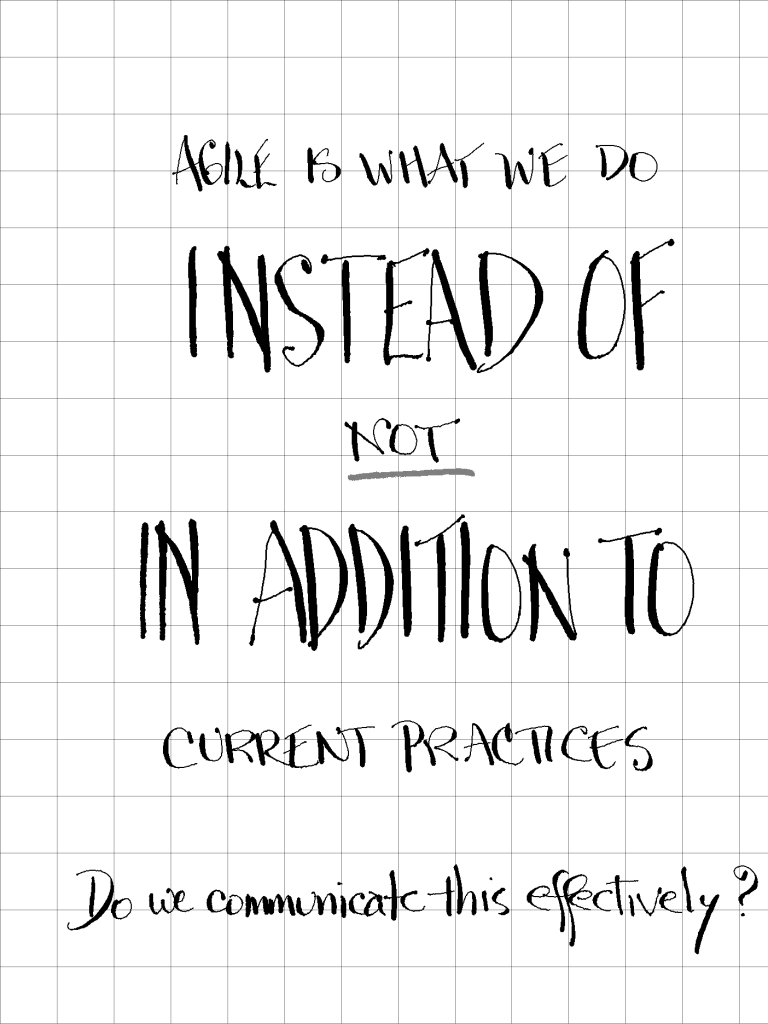

In my long-ago Scrum training, people from a large financial institution, objected to almost everything our instructor told us. “We can’t do that,” they whined. “Audit won’t let us.” I might have called out, “How do you know? Have you asked them?”

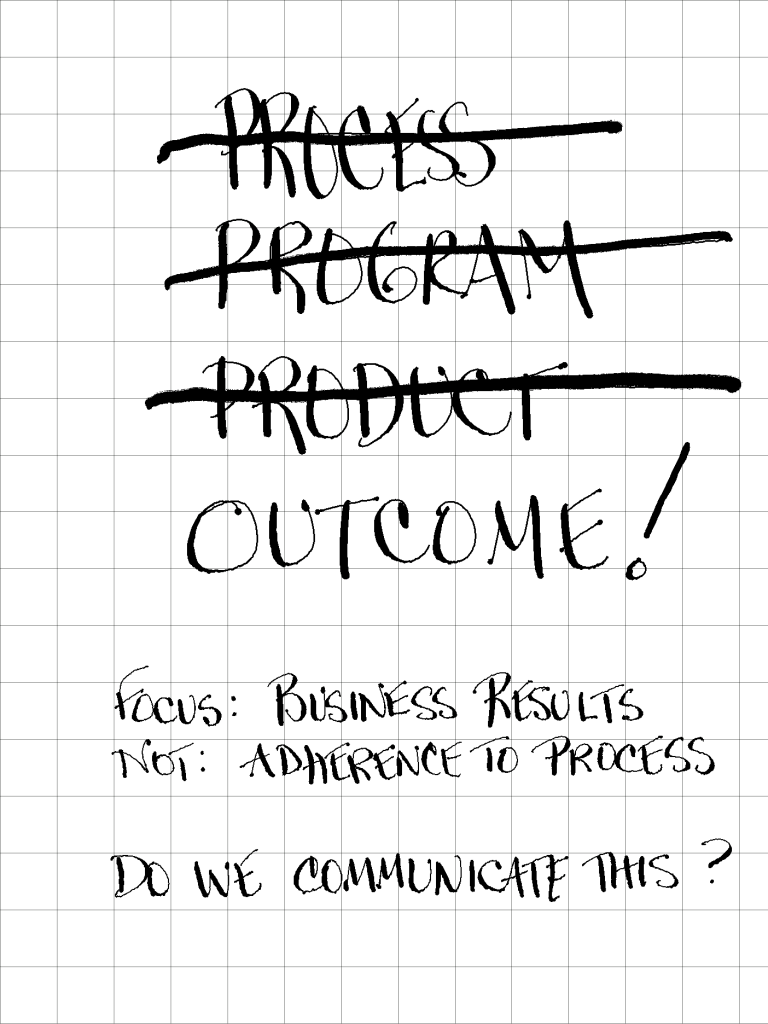

As Agilists, our role is to improve the way people work, not add to their burden. Certain reporting requirements and other practices become redundant when teams work in an Agile way. Does the corner office really need that status report when they can see the work board? Is this security practice still relevant?

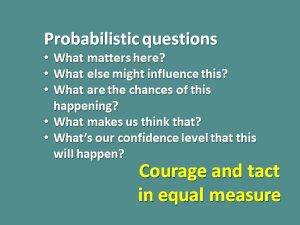

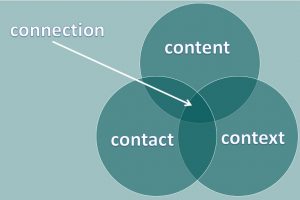

Conversations with our bosses, partners and clients can create realistic expectations. Can we hold them? Do we hold them? The same sort of conversation can help us – and our bosses, partners and clients – understand whether agile practices and actually address the business problem. Or which practices address it and which add no value.

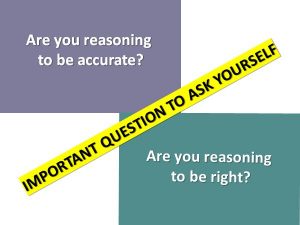

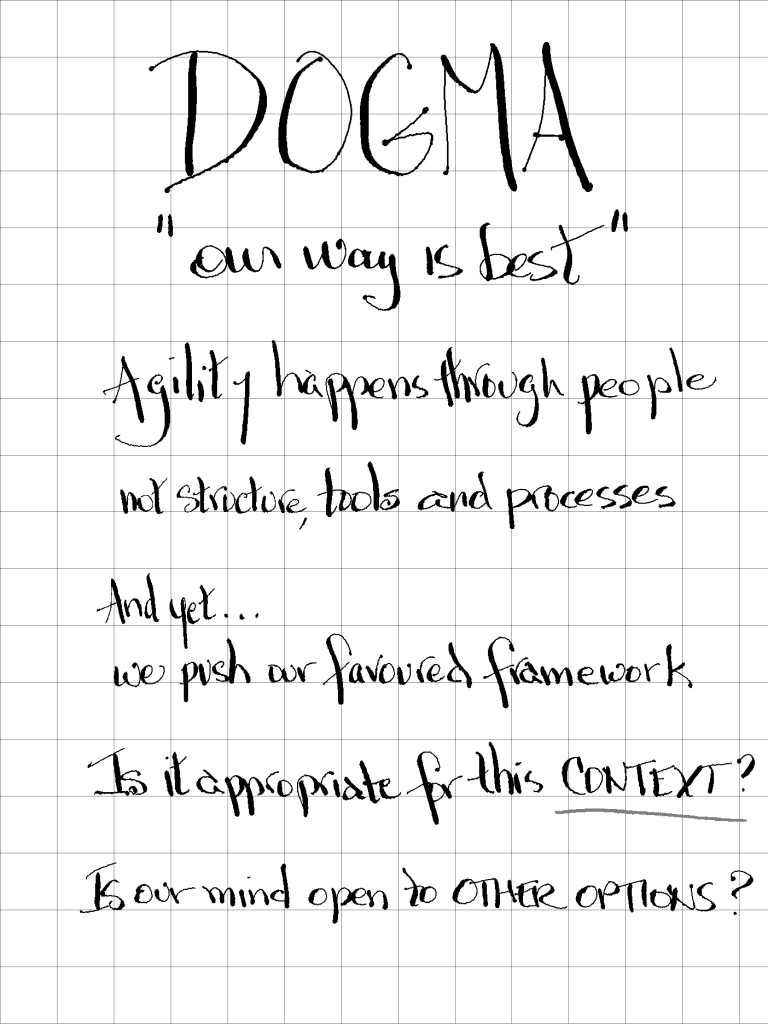

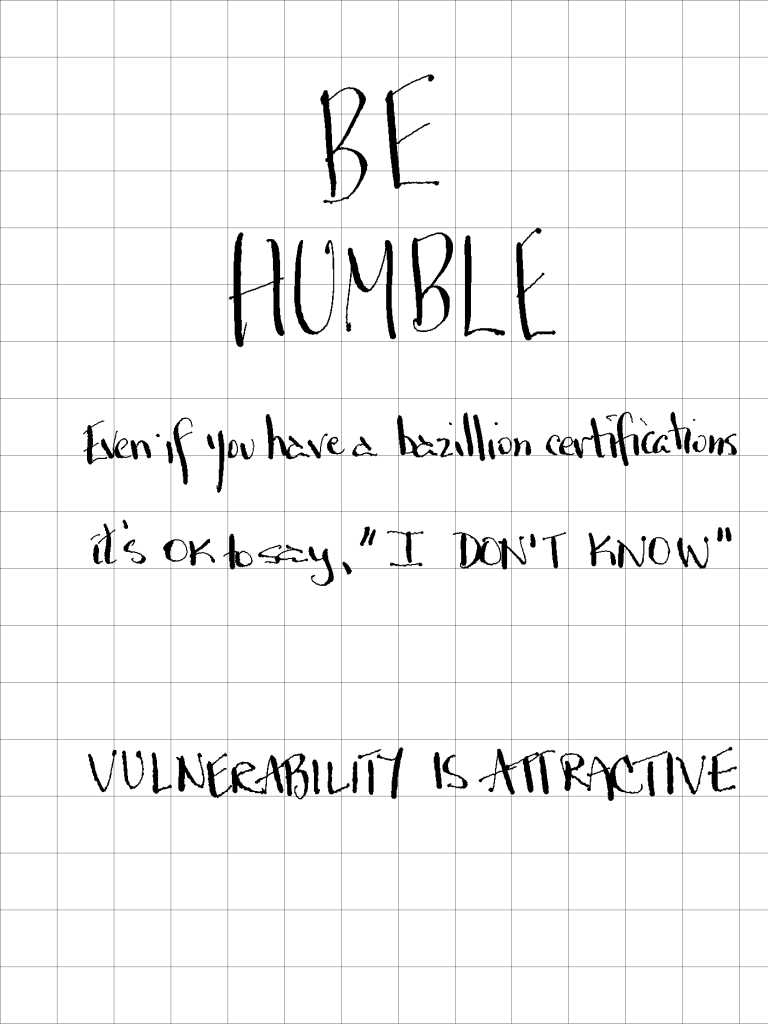

One of the most disturbing things I have observed is a sort of “Agile Arrogance.” I see Tweets about, “these guys just don’t get it,” and comments about “management morons.” Why are some people so dismissive about people who don’t buy the ideas they’re selling? (Recall the dogma section.) I suspect they define success in their jobs as “people do what I tell them.” Is that really the deal? We are hired and paid for our expertise and experience. We offer our best support in the best way we can. People, including those who hired us, won’t always take it. Recall Jerry Weinberg’s Third Law of Consulting: “Never forget they’re paying you by the hour, not by the solution.” Our job is to make the offer. We offer our mad programming, facilitating, coaching, change management and people skills and experience.

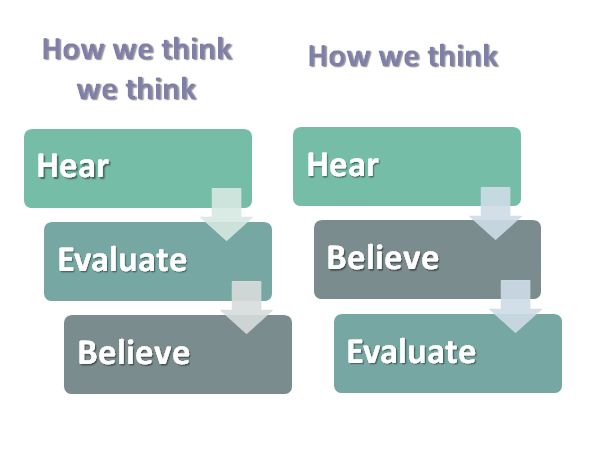

These things we offer are more likely to be appreciated, and our support accepted, if two other traits are in place. You can’t be certified in them and they may not show on your resume. But people know when they are present. They’re worth discussing – and practising – if we are to improve our profession and our own chances of success as practitioners. We need to develop humility and curiosity in ourselves and nurture these traits in others.

We need conversations about all these things, where we use empathy and confidence, in equal measure. What I’ve seen, in over 50 years in the workplace, is that real confidence comes from knowing you don’t have all the answers and being OK with that because you’re going to find them – or you’ll find something better on the way.

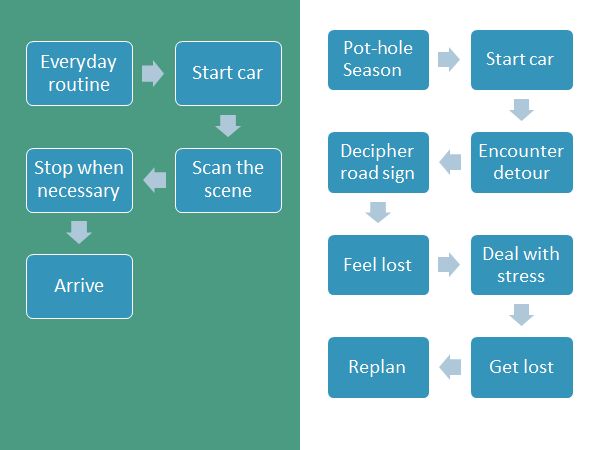

Perhaps it does that. But do we know? Do they know? When we have a constructive, two-way conversation about the practices they and we are introducing, we contribute. Do we wait for the all-singing, all-dancing, all-ducks-in-a-row. super-technicolour Agile solution to come along, all signed-off and budgeted and staffed up with seals of approval all over it? Change does not have to be a big, hairy deal. We can make change non-threatening – for everyone – by framing change as an experiment. “Let’s try this small thing for a short time and see if it works. We’ll learn something. We’ll use the people and budget we already have. And, if it doesn’t help, we’ll stop it.” Nothing will convince people you are serious about experiments and empiricism like cancelling a change that didn’t work out.