by Susan Johnston | Nov 7, 2021 | Build your own skills |

In Being Wrong – Part One, we looked at some of the reasons – both innate and learned – that contribute to our “need to be right.” In this post, we’ll look at some things we can do to stop it from getting in the way of good decisions.

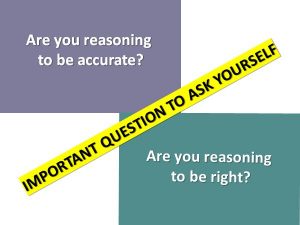

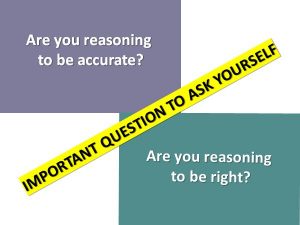

One of the first things we can do is to be aware of whether we are reasoning to discover something or to confirm something we already believe.

Whether we’re playing poker, building software, introducing organizational change or deciding which checkout line to go into at the grocery store, we’re working with incomplete information. There is lots of uncertainty. Lots that we can’t control, no matter how smart we are.

Thought experiment

- What was the best decision you made in the past year?

- What was the worst decision you made in the past year?

- (What was your process for making each decision?)

Today’s environment, for work and for life is volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous. We can’t be certain how anything we plan will actually turn out. Still, we have to take a chance and bet on something.

We can develop practices that will help us overcome our habits and biases so that we improve the odds in our decision making. Help us make better bets.

One recommendation is to cultivate what are called “Negative capabilities.” It’s a strange label because there is nothing negative about these traits except they are less visible and action oriented than those normally associated with success. They’re not the sort of thing we normally put on our résumés. It was the poet John Keats who first used the term and it’s been adopted by psychologists (such as Wilfred Bion) to indicate openness of mind, the ability to tolerate the pain and confusion of not knowing, rather than trying to be certain in an ambiguous situation.

They’re not the sort of thing we normally put on our résumés. It was the poet John Keats who first used the term and it’s been adopted by psychologists (such as Wilfred Bion) to indicate openness of mind, the ability to tolerate the pain and confusion of not knowing, rather than trying to be certain in an ambiguous situation.

Both “positive” and “negative” capabilities are needed to create a space of learning and creativity.

Source: French, Simpson, Harvey – “Negative Capability: A contribution to the understanding of creative leadership” (2009).

You exercise these negative capabilities when you challenge your beliefs

- What are some of your typical reactions when you come to the edge of your knowledge and expertise?

- What might you begin doing if you were not afraid of looking or being incompetent?

- When was the last time you said, “I don’t know?”

- What would be a safe context in which you might express doubt?

- How could you test your assumptions?

- How might you show more compassion to yourself and others when facing the unknown?

Source: D’Souza & Renner – “Not Knowing” (2014).

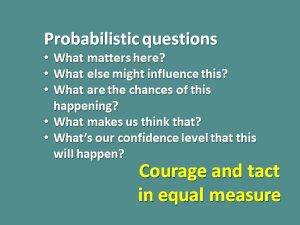

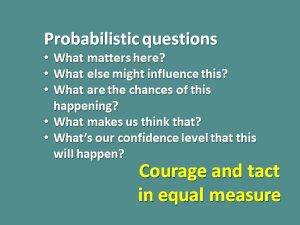

Decision making can be improved by adopting probabilistic thinking. This is essentially trying to identify the most likely outcomes of a course of action. Data specialists use modelling tools, math and logic to estimate the likelihood of any specific outcome coming to pass. I’m not advocating for us all to go out and become data scientists, but we can make an effort to calculate the odds in uncertain situations and assess the risk of choices. This is a good team or group exercise.

The first question to ask is, “What matters here?” You want to the identify situational conditions that will affect the outcome – as many as you can.

For each one, ask “What are the chances of this happening?” based on your knowledge of the facts relating to that condition and actual experience in similar situations. Attach a confidence level. “How confident are you?” (You could use your Planning Poker cards.)

Identify the assumptions you’ve made and assess their reliability. Think about any cognitive biases that might be at work. Then make the decision.

Watch your language

- Ask humble questions, not rhetorical or smart-alec questions.

- Challenge your own ideas – train yourself to test alternate hypotheses

- Focus on accuracy

- You might be wrong

- Be open to diverse viewpoints

- Work in groups – easier to see others biases than our own.

- Give everyone permission to ask, “What are we not seeing? And why?”

Other sincerely curious questions

- What is likely to happen if we do X? What’s our level of confidence?

- How do we know? What’s our evidence?

- What would need to be in place for that to work?

- What else might be true?

- How can we find out?

- What are we not seeing?

- Are we examining for discovery or for confirmation?

- What biases do we have that might lead us astray?

Use the team. You might build this sort of questioning into your team agreement so curiosity and humility become the norm. It will help you go from trying to be right all the time to seeing a more accurate and objective representation of the world.

Developing the habits of exposing our thinking, acknowledging and neutralizing our biases, and recognizing the value of not having all the answers requires deliberate, conscious practice. It’s worth it. It calls for courage and tact in equal measure. It wakes up our brains so that we build a better foundation for our bets.

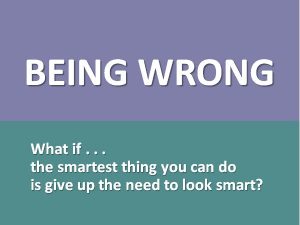

Sometimes the smartest thing you can do is give up the need to look smart.

by Susan Johnston | Nov 7, 2021 | Build your own skills |

This post is based on a presentation Sue gave, in 2021, at an internal Agile conference at one of the Canadian banks.

I’m willing to bet that you’ve discovered that your interactions with colleagues and other departments are as important to Agility as the work you do. It often is the work.

Communication is key to our collaborative and iterative way of working. And sometimes it doesn’t go so well.

Sometimes, we get in our own way, trapped by a very human desire to look smart that impedes our decision making.

In this post, we’ll look at ways you can limit their influence. We’ll answer the question, “What if the smartest thing you can do is give up the need to look smart?”

First – a thought experiment. Think about the way you drive. Are you better than average, about average, or worse than average?

Would it surprise you that something like 80 per cent of people believe they are better than average drivers? It cannot be true. Do the math.

This phenomenon has been validated by lots of research. Eighty-seven per cent of Stanford MBA students believe they are smarter than others in their program. This trait shows up in studies of stock traders and lawyers. Worse, Kruger & Dunning, discovered that people who considered themselves the smartest in their groups were, in fact, at the bottom.

This phenomenon is known in social psychology as “illusory superiority.” We overestimate our own ability in relation to the same thing in other people. And we underestimate theirs.

Illusory superiority is one of many cognitive biases affecting decision making. Consider, for a moment, where illusory superiority may or does show up in your life. In your work. On your team.

So, it seems there’s a natural human trait that makes us think we’re smarter than we are. And our brains support us in this.

Because our brains are lazy.

Legions of neuroscientists have hooked human brains to technology that shows our brains are set up to expend as little energy as possible. There’s no shame in this. Our earliest ancestors needed that energy for survival in a harsh world beset with predators and lots of danger. They had to muster the physical and mental capacity to always be ready to fight or to flee – and to decide in a split second, which of those was the better option. Their brains didn’t have time to think things through and, instead, they took shortcuts.

Centuries later, your brain still does this.

In his book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman describes experiments that show how our brains resist processing new information. Our brains see patterns, sense similarities and use memories of familiar patterns to guide our behaviour. It’s almost automatic, beneath our awareness.

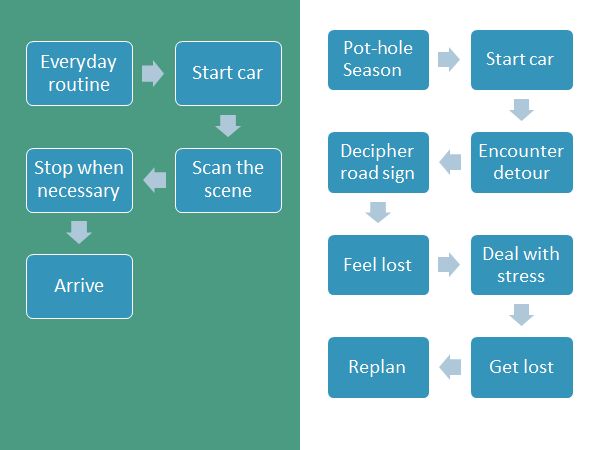

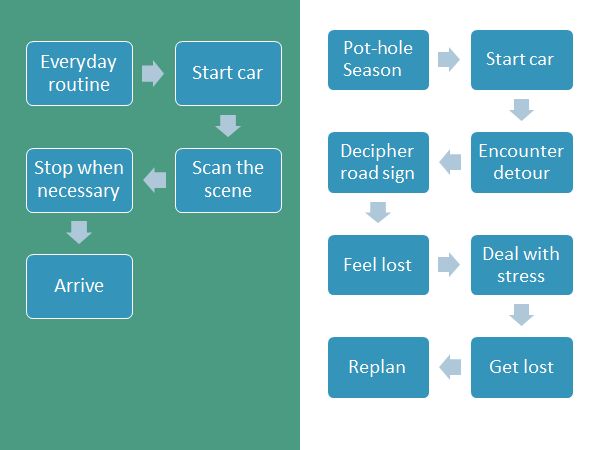

Let’s go back to driving, if you travel the same route every day, beyond watching the road, you may not be aware of your actions. Your brain doesn’t have to work at thinking. It uses well-worn neural pathways to respond quickly and guide you from start to finish without using up energy. But if there’s a detour and you need to follow signs, your brain must work to process new information. And it’s a slower, more challenging, process since your brain hasn’t done this before. It must take the energy to consider the info and make decisions.

Here’s another thought experiment. How can you tell a dog’s age? Well, you take its chronological age and multiply by seven. How do you know? Everybody knows that. Really? Turns out it’s wrong. But our lazy brains believe it because we heard it somewhere. Rather than challenge the idea, do some research, or even think about it, we bought the idea. After all, it made sense.

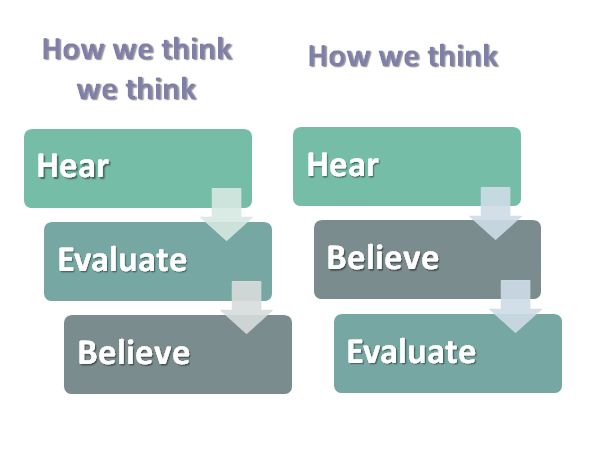

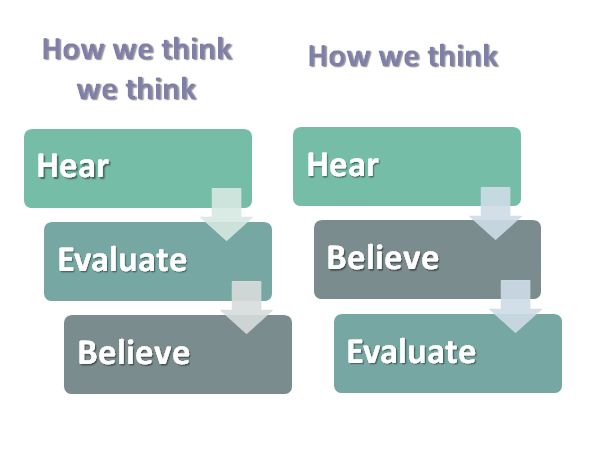

Our brains fool us that way. We assume it works like this. We hear something. We evaluate it. We believe it. What’s really going on is this. We hear something. We believe it – especially if we hear it from someone we trust, someone in authority, or someone like us. Then we evaluate it. When we get around to it. If we have time. Later. Maybe.

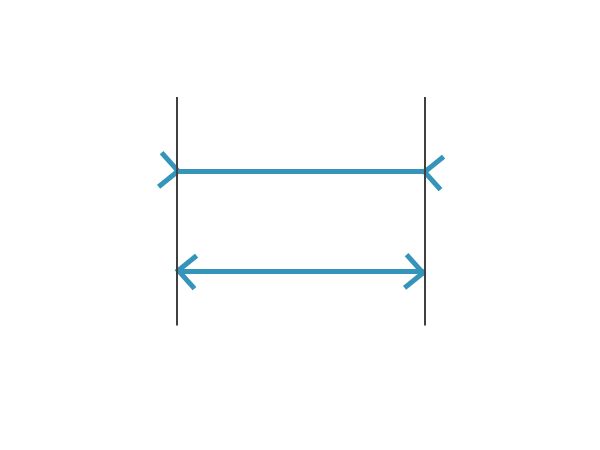

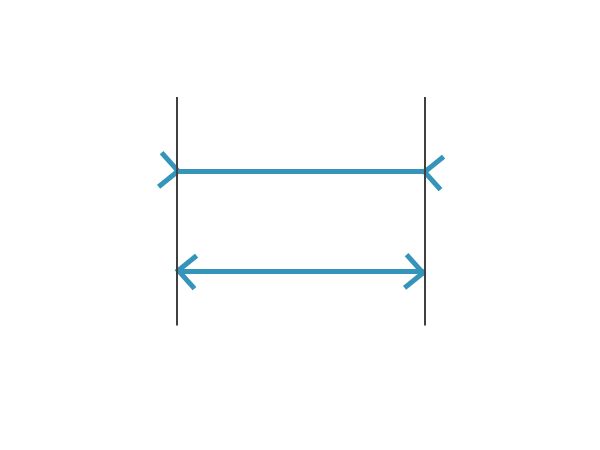

Our brains also make stuff up. There’s a well-known optical illusion where two lines of equal length look very different because the ends of one point inward and the ends of the other point outward. The outward pointing line appears longer. Measure the lines and you see they are the same length. But our brains have trouble with that.

This illusion is an example of another cognitive bias. Confirmation bias. Even when we have evidence that something else is true, we still may have a hard time believing it.

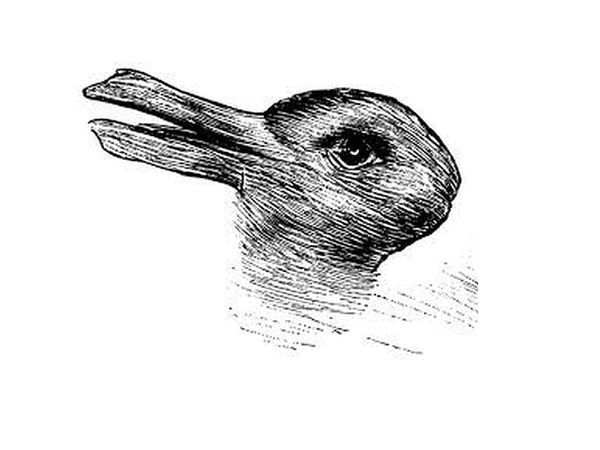

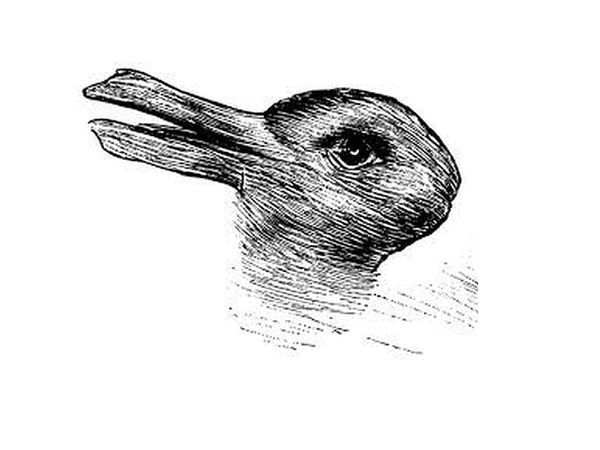

Your brain may also misperceive things, especially when information is incomplete. It’s looking for patterns. In this illustration, what creature do you see? Is it a rabbit? Is it a duck? Who knows?

This bunny/duck dilemma also reminds us that every brain is different. The way you perceive and believe things affects your decisions and behaviour. This is relevant to collaboration – a key element of working in an Agile fashion.

If I see things one way and you see them another, the conversation can get messy and collaboration’s at risk because of another human characteristic – the need to be right.

The brain’s discomfort with information in patterns it doesn’t recognize is one of the reasons people may resist new ideas when they’re first presented. The brain will often ignore new information. It’s uncomfortable to think through something new and different. It uses up resources. Once we decide something is true, we really don’t want to change our mind about it. That’s another cognitive bias.

It gets worse. Even when we look for the truth, we’re often really looking for support for our own existing beliefs.

by Susan Johnston | Jan 11, 2016 | Build your own skills, Get people talking |

Face-to-face communication is the most powerful business tool we will ever have. So why don’t we use it more often? Or more effectively? Or more consciously?

For over a decade, I’ve been encouraging people to get out from behind their tools and technologies and talk to each other. People nod vigorously. Then they send off an e-mail with a .ppt attached. Or they type something into Jira and feel the product user’s needs are well described. Maybe they post a Tweet, hoping the right people will read it. Have you ever said, “Yes, I talked to [Whomever],” then recall later that what you actually did was correspond in Slack? Tools can fool us into thinking we’re communicating.

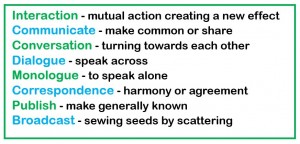

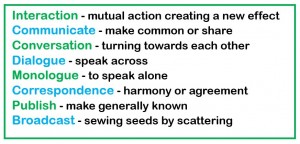

Tools create contact. They can also share certain kinds of information. That is all. We mustn’t confuse that with connection, communication, conversation, dialogue or real interaction that leads to fresh ideas or new ways of working. Yet we do. We see a situation that will create a problem for our project and we send a memo. We need executive support for an initiative and we give them a PowerPoint. We would rather type than talk.

Tools create contact. They can also share certain kinds of information. That is all. We mustn’t confuse that with connection, communication, conversation, dialogue or real interaction that leads to fresh ideas or new ways of working. Yet we do. We see a situation that will create a problem for our project and we send a memo. We need executive support for an initiative and we give them a PowerPoint. We would rather type than talk.

When we use text, whether it’s paper, email, text messages or something else, we may be transmitting information, but not necessarily communicating. Even when we actually are together, we can fail to communicate. Are your meetings a series of broadcast monologues? “I did this yesterday. I’m working on this today. Nothing’s blocking me.” Or do people actually talk about the work they are doing together?

The first value of the Agile Manifesto for software development emphasizes “individuals and interactions over processes and tools.” The meaning of the world “interaction” is a mutual or reciprocal action. In its scientific meaning, it’s a situation in which two or more objects or events act upon one another to produce a new effect. That’s the sort of thing that can happen in a good conversation.

But it’s easy to be distracted by our tools and processes. Maybe it’s because these are things we can measure. Are we having daily stand-up meetings? Tick the box. Retrospectives after every sprint? Tick again. All user stories in the system? Another tick. Tools and ceremonies are useful in creating good work, but they are not going to substitute for a conversation. At best, they can provide a reason to talk. We say, “A user story is an invitation to a conversation.” Do we truly understand what that means?

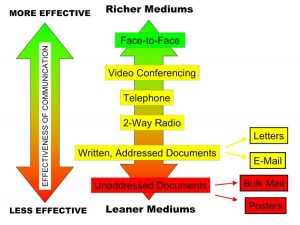

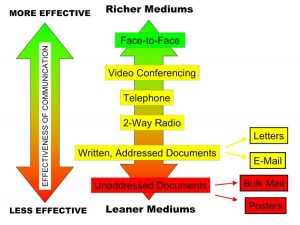

The Media Richness Theory, developed in corporate communications in the mid-1990s, ranks communication methods according to how well they reproduce the information sent through them. Face-to-face communication sits at the top. When we’re talking together, we have the benefit of emotional and social cues, through body language and tone. Importantly, we also have a very short feedback loop. We know, at once, if our message has been received. We also have the opportunity to ask for and provide clarification and confirm understanding.

The Media Richness Theory, developed in corporate communications in the mid-1990s, ranks communication methods according to how well they reproduce the information sent through them. Face-to-face communication sits at the top. When we’re talking together, we have the benefit of emotional and social cues, through body language and tone. Importantly, we also have a very short feedback loop. We know, at once, if our message has been received. We also have the opportunity to ask for and provide clarification and confirm understanding.

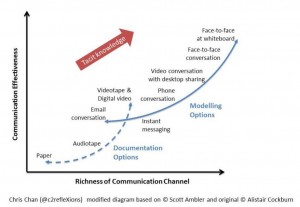

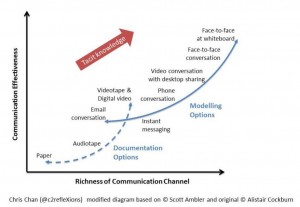

More recently, Alistair Cockburn created a similar model, based on his own observations on projects. Modified, first by Scott Ambler, later by Chris Chan, it suggests that having a meaningful visual depiction of the information adds even more richness.

A conversation at a white board, for example, can provide even more meaningful conversation than conversation alone. We have all the richness of a face-to-face conversation with the additional ability to visualize and manipulate information as we discuss it.

A conversation at a white board, for example, can provide even more meaningful conversation than conversation alone. We have all the richness of a face-to-face conversation with the additional ability to visualize and manipulate information as we discuss it.

Some of the most productive conversations are those that are well facilitated. A good facilitator creates a container for thinking together and makes it safe for people to express their ideas. Facilitation provides enough structure to engage people and enough freedom for them to be creative. It encourages full participation and ensures the outcome of the discussion is “owned” by the group and can be implemented. While it often falls to the agile coach or scrummaster, facilitation can be anyone’s job. Helping people talk together is a learnable skill that will increase in value as teamwork and cross-functional collaboration become the norm.

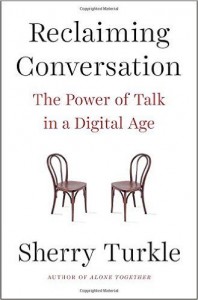

Can we recover the art of conversation? Generations of thinkers and writers have moaned that conversation is becoming a “lost art.” There’s new evidence that it’s true. The most recent call to action comes from Sherry Turkle in her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York). A sociologist, psychologist and MIT professor, she’s been observing the impact of technology on society for over 30 years. She contends that our tools, particularly our “always on” mobile devices, are limiting our ability to hold meaningful, impactful conversations.

We can rediscover and recover this dying art by reminding ourselves of the importance, impact and value of real conversation as a workplace tool – and then doing something about it. We can recognize our tech tools and processes for what they are – processes and tools. We can use them for their intended purposes – but not indulge in the illusion that we are interacting when we use them. Step away from the screens, apps and devices. Step towards the white board with someone who matters. Can we talk? You bet!

In case you missed it: Can we talk? Getting back to conversation – Part 1

by Susan Johnston | Jan 9, 2016 | Build your own skills, Get people talking |

Ten years ago, my writing and conference talks were filled with predictions that conversation would be the Next Big Thing.

2007

Citing evidence from multiple disciplines, I called for organizational leaders to recognize that the desire for connection is a basic human trait and make in-person interaction a deliberate priority. Instead of trying to master blogs, podcasts, email and other tech-centric communication channels, I urged them to get out and talk to people.

But Next Big Thing would not be face-to-face communication. In 2007, along came the iPhone. Mobility became the NBT. And our world changed. Today, our mobile devices keep us “connected” and “talking” to people around the world 24/7. Yet, is it a true connection?

In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York), sociologist/psychologist and MIT prof Sherry Turkle suggests our “always on” connections, such as facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thousands of other apps, provide the illusion of communication, but actually impede conversation. We can avoid real conversation by sending a text. We can post a picture rather than engage with someone. We can edit ourselves into a carefully constructed persona that presents someone we are not and will never be. We can post messages to facebook “friends” while ignoring the real friends in the room with us. We can get attention without the unpredictable untidiness of getting close.

In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (Penguin Press, New York), sociologist/psychologist and MIT prof Sherry Turkle suggests our “always on” connections, such as facebook, Instagram, Twitter and thousands of other apps, provide the illusion of communication, but actually impede conversation. We can avoid real conversation by sending a text. We can post a picture rather than engage with someone. We can edit ourselves into a carefully constructed persona that presents someone we are not and will never be. We can post messages to facebook “friends” while ignoring the real friends in the room with us. We can get attention without the unpredictable untidiness of getting close.

A Gloomy Outlook?

Turkle has spent 30 years investigating our society’s relationship with technology. In this book, her ninth, she descibes offices where workers lay out their multiple devices, don headphones and spend the day exchanging electronic messages in isolation. She describes the “rule of three” – as long as three people in a face-to-face group are actually talking to each other everyone else can be looking at their phones. She quotes people who conduct family discussions by text so they can “fight without saying things [they’ll] regret” – and have a record of who said what. She describes toddlers competing with mobiles for their parents’ attention, new moms texting while nursing newborns, and children who talk about what’s on their phones rather than what’s in their heads. What worries her most is her belief that we are losing the ability to hold real, meaningful conversations.

IBM’s PROFS

Turkle’s work made me examine my own relationship with online communication tools. I’ve used them since pre-Internet days, when I sent email-ish things on the green screens of mainframe terminals. Today, I used tools in “The Cloud,” wherever that is, that we could scarcely imagine 10 years ago – Slack, Twitter, Trello, Ruzuku, Zoom and more. (I’m still waiting for “Beam me up, Scotty.”) They’re handy, yet today’s most valuable and rewarding connections were in cafés, face-to-face with colleagues and clients. I could look them in the eye, feel their energy, sense their presence, offer my full attention and really be with the people I chose to be with.

Text is fine for transmitting information, but it’s not the tool for real communication. A recent text exchange led friends to a weird misunderstanding. Words intended as heartfelt encouragement came off as preachy. The carefully crafted response was interpreted as a snotty retort. Nuance, subtlety, emotion, energy – all missing. Words are not enough. How often have we spent hours crafting careful responses to emails when we should have just picked up the telephone and sorted it out through conversation?

So what can we do?

Which brings us back to Turkle and Reclaiming Conversation. She paints a bleak picture, yet offers hope. We don’t need to give them up, but we need to choose how we use these devices. We can designate tech-free zones, declare a mobile moratorium during meals, establish no-device hours, banish them from meetings. She writes, “If a tool gets in the way of looking at each other, we should use it only when necessary. It shouldn’t be the first thing we turn to.”

We can ask ourselves if our relationship with technology is helping us live better, more fulfilling lives or getting in the way of important moments and real connection. Our insights about the way we use our tools will guide us. The art – make that the gift – of conversation is too important to lose.

Can we talk? Getting back to conversation – Part 2

by Susan Johnston | Jan 24, 2014 | Build your own skills, Get people talking |

SCARF is a concept developed by David Rock of the NeuroLeadership Institute and popularized in his book, Quiet Leadership. It’s a good way to take stress out of a conversation. That’s useful, since a person in stress doesn’t think clearly.Sometimes, our brain is not our friend.

SCARF is a concept developed by David Rock of the NeuroLeadership Institute and popularized in his book, Quiet Leadership. It’s a good way to take stress out of a conversation. That’s useful, since a person in stress doesn’t think clearly.Sometimes, our brain is not our friend.

There’s a busy and primitive part of it, the amygdala, always scanning for changes in the environment. It interprets all change or discomfort as danger, which made sense when the User Guide for Life  was: “Eat or be eaten.” When the part of the brain concerned with survival takes over, the “fight or flight” mechanism kicks in automatically. The part of the brain that processes information and makes decisions is all but shut down as the body involuntarily prepares for trouble.

was: “Eat or be eaten.” When the part of the brain concerned with survival takes over, the “fight or flight” mechanism kicks in automatically. The part of the brain that processes information and makes decisions is all but shut down as the body involuntarily prepares for trouble.

The theory suggests there are five elements of a relationship or situation that can derail any conversation if they are missing or out of balance. The more we can do to provide them, the more likely the other person is to feel safe in the conversation and able to think clearly.

You won’t be surprised to learn that SCARF is an acronym.

STATUS – “Where am I in the pecking order?” Our brains are always on the lookout for evidence of where we sit regarding power, authority and influence. That’s residue from an earlier time, one that held greater risk of getting clobbered. We feel safer when we sense that our status is equal to or greater than the folks around us. Neuroscience suggests that our brains react to a threat to our status the same way they do to a physical threat. The brain doesn’t differentiate. So if you “outrank” the person you’re talking with – you’re their boss, professor, parent, etc. – the very fact of talking with you is stressful because your status is higher than theirs.

What can we do to balance the status? Recognizing the gap is the first step. You might move the meeting from your office to a neutral place or a place where they are comfortable. A conference room, a cafe, their office or go for a walk. You might draw their attention to a fact that raises their status. “I need to talk with you because you have experience with this project.” “Your job gives you a closer look at [whatever], so I value your thoughts.” “As a member of this team, your work is important to our success.” Make it something real – they’ll smell inauthenticity.

(more…)

by Susan Johnston | Jan 24, 2014 | Build your own skills |

Holding a good conversation is the best way to instigate change for the better. People hear what’s going on, issues are aired, confusion is cleared up, everyone goes away happy, and change goes smoothly.

Holding a good conversation is the best way to instigate change for the better. People hear what’s going on, issues are aired, confusion is cleared up, everyone goes away happy, and change goes smoothly.

On what planet?

While humans are naturally wired to communicate, we’re not all set up to do it well. You don’t have to look very far to find an example of miscommunication that leads to waste – wasted time, wasted effort, wasted energy, wasted goodwill.

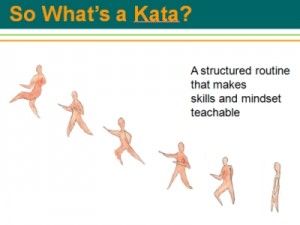

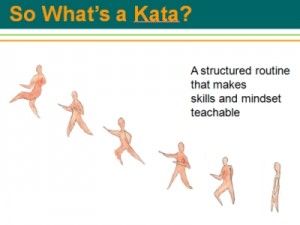

Fortunately, there are some key behaviours we can learn and practise that will increase the chance that our communications will be heard, understood and acted on. We call these “Communication Kata.” They’re named after the exercises practitioners of martial arts, such as Aikido and Kung Fu, repeat, over and over, until they become instantly available to them when needed. They don’t have to think, “Now I move my right hand here and raise my left foot so many inches.” They focus on strategy. “Now I kick my opponent in the back.”

Similarly, learning and practising these communication kata makes these techniqes of effective interaction available whenever you’re in conversation. You don’t need to think about the process, you can focus on the content. Think of it as “Tongue Fu.”

We’ve presented these Communication Kata at conferences (Agile 2013 and Agile Tour Montreal). By popular request, we share them here on the blog.

Communication Kata 1: SCARF

Communication Kata 2: Share your intention